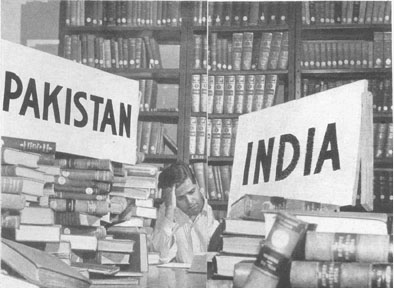

When India

and Pakistan were born in 1947, many in the sub-continent hoped the cycle of

hatred which partition of the sub-continent had unleashed would like most conflicts, come to an end. That has as yet not happend, perhaps because of the nature of

the theory which gave birth to Pakistan.

What many fail to understand is Pakistan, India's twin

brother, was born as an anti-thesis of all that India stood for. India’s

leadership envisaged the nation would be a federal, multi-lingual, multi-racial,

secular state. The Pakistan theory envisioned just the opposite – a unitary

state where one religion and one language and left unsaid – one race - would

determine nationhood and citizenship.

Its founder,

the otherwise secular in his personal

life, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, tried to undo some of the damage that this theory

could wreak on the child he was giving birth to by trying to `secularise’ state

policy. In a remearkable speech to the Constituent Assembly

of Pakistan, Jinnah said “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you

are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State

… no distinction between one community and another, no

discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with

this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one

State.”

However, his death soon after

Pakistan’s creation put an end to that start.

The Pakistan theory’s

raison-d’etre was in negating all that India stood for. If Muslims and Hindus

could get along together, then Pakistan’s logic was lost. To undo the enmeshed

twinning of the two faiths’ adherents, Muslim League and its ideological followers, worked overtime, helped, many allege by Britain, the fading power which wished to continue its rule through a policy of `Divide et Impera'.

Through the

1930s and ‘40s, in Bengal and Bihar, Muslim women were asked to replace wearing

red bordered saris with green bordered ones, in Western and Northern India to replace

saris with salwarkameez. Bindis were frowned upon. Muslim boys were asked to

stop wearing dhotis and opt for Payjamas. (How these were deemed more `Pakistani' is

still a mystery). The idea was to create separate identities.

In 1947 it

seemed to work. Identity politics reinforced by communal violence saw the

country partitioned.Three fifth’s of the sub-continent’s Muslims lived in the

Punjab, Sindh and in the North West Frontier Province or in East Bengal. They

opted out of India to follow Jinnah into Pakistan. Those who said otherwise,

such as Badshah Khan or the Baloch of Kalat, saw their voice and reasoning

drowned by the voluble cries for Pakistan.

Millions

more caught on the `wrong’ side of the border, followed the paths of the greatest human migration in history. Post-partition, non-Muslims

were less than 5 per cent in West Pakistan and about 29 per cent in East.Through

the 1950s and 1960s, with increasing marginalisation and occasional progroms,

minorities kept migrating from there to India, bringing down their numbers to

about 14 per cent in East Pakistan by late 1960s and two and a half per cent in

West Pakistan.

Indian Muslims : Indians first

Pakistan after

coming into being,had started defining who was a Muslim. Ahmedias and Bohras

lost out early in this search for the `Pure’. Later Shias were discomfited by

questions of how true their Muslim identity was and in recent years subjected

to ethnic cleansing attacks.

Ethnicity

was also a moot question. Pakistan

defined itself as nation which inherited India’s Arab and Central Asian

heritage. This, seemed to suggest that Pakistanis were descendants of the `Golden

hordes’, the Arab, Turkic and Moghul armies which came to India in medieval

times.

At best this was but a scatter-brain theory which chose to ignore that most Indian Muslims

were descendants of converts to the new, attractive monotheistic

religion, which gave many Indians an alternate to the decadent,

caste-ridden form of Hinduism which flourished when Islam entered India. However, this` hypothesis' at one stroke, immediately

marginalised the already poor, dark complexioned émigré’ from India and the Bengali Muslims of East Pakistan.

The search

for `Purity’ threw up an oligarchical leadership in the neighbouring state – a

coterie of Punjabi-Pathan and high born émigré’ from North India feudals who

controlled the top rungs of the army, bureaucracy, industry and politics in

that country.

Challenges to the Idea of Pakistan

Racial discrimination, insistence on one language, Urdu, economic colonisation of the East by the West, lack of democratic outlets to grievances, led to Pakistan breaking up and giving birth to Bangladesh. Ethnic identity politics still remains a bitter divide in Pakistan, with poor émigré’ Bihari Muslims living in Karachi slums often erupting in violence against real or perceived discrimination.

The challenge whch the formation of Bangladesh gave to the theory that Pakistan, was the sole refuge for Muslims of the sub-continent, who

in the eyes of Pakistan's founders were a separate people set apart from their

neighbours, was met by a stricter interpretation of the `Pak (Pure)’ theory.

Children were taught through official textbooks from the 1970s onwards, that

Hindus were their enemies and that history started with the Arab invasion of Sindh, which saved

people from a despotic, harsh Hindu rule. Earlier eras and civilisations were simply

forgotten.

Non-Muslims

and Muslims, not deemed to be Muslim enough, were further marginalised and laws

and regulations changed to ban liquor, cabarets, Hindi movies, shared festivals, in short

anything which was shared fun.

If India was

successful as a secular nation, then Pakistan’s logic was lost. Hence

Pakistan’s need to challenge the accession of Kashmir, India’s only Muslim

majority state. Two wars by Pakistani armed forces could not detach the state.

Rather, the state through repeated democratic elections seemed to renew its

faith in a life with India. In the late 1980s, Pakistan therefore started

fomenting trouble in Kashmir valley. The

result was not really in favour of Pakistan, but it was against Indian unity.

A secessionist, Islamist, movement took roots

in the valley, partly because of Pakistan’s proxy war, partly because of

genuine long standing discontent arising from a series of corrupt state

governments, economic deprivations, Central neglect, etc.. A challenge, the

Indian state has tried to meet partly by using military force and partly by a mix of talks with separatists and

steps to better the economy of the state.

However Kashmir

represents just 10 million of India’s more than 160 million Muslims and Kashmiris seem to believe more in their Kashmiriat than their religious identity.

Radicalising the larger body of Indian muslims and using this mass as a bulwark against India was

therefore always an even more attractive option for those who wished to reinforce the

two-nation theory.

Unfortunately

for them, this proved to be a difficult option. Most Indian Muslims thought of

themselves as Indians first and Muslims afterwards and certainly had little or

no sympathies for Pakistan. The valour of Indian Muslim soldiers in 1948, 1965,

1971 and more recently in Siachen and Kargil are testimony to that as also the

immense contribution of that community to India’s administration, politics,

theatre, the arts, literature, academia and sciences.

More recent

attempts of using morphed images of Thai, Tibetan and Chinese to represent

Rohingya and Assamese Muslim riot victims to inflame passions through India,

too seems to have fallen flat on its face.

The unity of

multi-racial and multi-ethic India was also a challenge to Pakistan which was

trying to create a single Pakistani Muslim identity with links to an Arabic-Central Asian heritage. Hence, Pakistan’s support

to rebel groups from the North East. First, when Pakistan was a united entity,

through camps in Chittagong Hills and later when a `Pak-friendly’ military

government was established in Bangladesh through a coup, by using other border

safe havens. Unfortunately, for Pakistan and luckily for India, Bangladesh in

the 21st century realised the dangers of allowing these groups which

brought drug peddling, money laundering and arms running into that state, a free run. A clampdown by Bangla authorities helped save that nation from a growing threat to its own safety and security, not to mention its relations with its

single largest neighbour.

Pakistan - Which Road Will It Take

As India becomes economically more successful and Pakistan sinks into troubled times with Baluchistan and Gilgit demanding autonomy at the least and independence at the best, Sindh turning more restive and Hill Pathan tribes dreaming of a greater Pashtunistan with their Afghan cousins, the idea of Pakistan will come under greater challenge. Desperate to reinforce its unity, that nation may well then continue on the path it chose earlier – challenging India’s unity and secular credentials to prove that the opposite of Pakistan does not mean success. India has her faultlines and these could well be exploited. Chosing this path will probably be concurrent with greater Islamisation or in effect even eventual Talibanisation of the Pakistan state.

If Pakistan,

choses this path, then it could mean more terror strikes at Indian targets,

psy-warfare of the kind witnessed in the recent sending of bulk SMSs to people

of North Eastern descent, threatening them with attacks by Muslim groups. The radicalisation of that nation will also

mean reinforcement of the feeling of victimhood in Pakistan, greater

intolerance towards other religions and people and greater support for ideas of

crusade or Jihad against not only India but also those perceived as Christian

nations.

However,

there is a different path that nation may chose. One of cooperation. It may

chose to befriend its twin brother to bring not only peace, but also prosperity

within its borders. One would hope it would chose that path. But, yes, that

choice will in time kill the idea of Pakistan as an anti-thesis to India. A new

identity will then have to be forged for that nation or else it would, in time, wither.

American

strategic affairs writer Robert Kaplan has pointed out that down the ages,

nebulous border states have often existed in the sub-continent, encompassing

border races and tribes, even as India proper has prospered as a single entity.

Perhaps Pakistan would like redefine itself as such a confederacy. The path it

choses in the next half a decade will be crucial for its existence and

well-being, indeed the well-being of the whole sub-continent.

Once the

choice is clear, India and other powers interested in Pakistan would react. If

Pakistan choses overt or covert confrontation as well as increasing

Talibanisation, India will have to rethink its peace propositions. These have

been made on the calculation that it is better to have one united neighbour,

with whom peace can be forged at some date on its western border rather than a

Balkanised, unstable region.

At some

stage, India, and other powers such as the US and Russia who face threats from

this rising tide of Talibanisation, will weigh the pros and cons of such a

stance and decide whether to risk a Talibanised Pakistan or to support the

process of Pakistan unravelling itself, risking the aftermath as a lesser evil.

6 comments:

Somewhat simplistic, I feel, since the creation of Pakistan and the bloody aftermath of partition was a complex chain of events, personality clashes and good old hand of the 'Empire' playing its last moves.

Also, regarding Kashmir, Pakistan has always wanted to keep the issue alive and India's wishy-washy handling hasn't helped. The upsurge in militancy during the 80's is also attributable to the sudden influx of the Mujahideen from Afghanistan, which had been funded to rout the Soviets.

Good write, Jayanta. Very lucidly presented... very logically argued.

...Kalyan Biswas.

A very clear and focused sketch of Inda Pakistan with well thought options to a very complex problem.

It was a one sided approach I felt.As usual we are very good at playing the blame game while taking away the focus from our leaders and their policies which have resulted in the situation.Did Jinnah alone carve out the nation? Are we not responsible for the Kashmir problem?What happened to the plebiscite promised by Nehru?Who is responsible for the Bangladeshi refugee problem in Assam?If only we would take out from our scams to reflect and instead of filling personal coffers think as a Nation.

I grew up hearing stories about the partition from our elders who had to move to New Delhi because of the partition. Reading Jayant's interpretation I feel it is well researched and very well written.

Thanks Jayant!

r

Post a Comment